Tandang Sora @ 200: Difference between revisions

Ascarbonilla (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Rsmoralejo (talk | contribs) m Tandang Sora @ 200 moved to Tandang Sora @ 200 |

||

| (5 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== | == Melchora Aquino == | ||

'' | ''Tandang Sora'' | ||

''' | '''AQUINO, MELCHORA''' (“''TANDANG SORA''”) (b. Banlat, Caloocan, Rizal, January 6, 1812; d. Manila, February 20, 1919 As told to the UP Diliman Committee for Tandang Sora @200 by her descendants on October 11, 2011. The descendants noted that this date is different from that recognized by the National Historical Commission.), “''Mother of the Philippine Revolution''.” As a young girl, she was so pretty that she was often Reyna Elena in santacruzans (Maytime festivals) and had such a good singing voice that she was invited to the pabasa (reading of Christ’s passion) even in neighboring barrios. Married Fulgencio Ramos, a cabeza de baranggay (village chief), and bore him six children, but was widowed at an early age. She not only assumed the role of father and mother but also managed the family’s farm. During the Revolution, she furnished the Katipuneros, who called her “Tandang Sora,” with rice, carabaos, and other supplies. She also nursed the sick and wounded. Fled to Novaliches, Rizal, was arrested and jailed, but steadfastly refused to reveal the whereabouts of Bonifacio and his men. Deported to Guam but later was repatriated by the Americans. Was offered a reward by the government for her patriotic services, but refused it though she was impoverished. Lived to the age of 107. <ref>Carlos Quirino. Who’s Who in Philippine History. Manila: Tahanan Books, 1995. Pp.32-33.</ref> | ||

===Grand Old Woman of the Revolution ''(1812-1919)'' ''by GERTRUDE D. CATAPUSAN'' <ref>[. Women of Distinction (Biographical Essays on Outstanding Filipino Women of the Past and the Present). Pp. 21-22.]</ref>=== | |||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

Through the ages of Philippine history, one reads of Melchora Aquino, otherwise known as “Tandang Sora.” | Through the ages of Philippine history, one reads of Melchora Aquino, otherwise known as “Tandang Sora.” | ||

| Line 10: | Line 11: | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

In her youth, Sora married Fulgencio Ramos, who later became a cabeza de baranggay. Their marriage was blessed with six children, namely: Juan, Simon, Estefania, Saturnina, Romualdo, and Juana. During their married life they were able to raise their economic status because of their extreme industry and frugality. However, their marriage was not to be for long, for it | In her youth, Sora married Fulgencio Ramos, who later became a cabeza de baranggay. Their marriage was blessed with six children, namely: Juan, Simon, Estefania, Saturnina, Romualdo, and Juana. During their married life they were able to raise their economic status because of their extreme industry and frugality. However, their marriage was not to be for long, for it ended with the early death of Fulgencio. Since then, Sora had to carry on, playing the dual role of a father and mother to their children. She also took complete charge of the family business undertakings. Again, her leadership and strong character were evident. Among her other virtues were courage, piety, industry, patience, and her sense of nobility. | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

Most noteworthy of Tandang Sora’s accomplishments was her being one of the energetic heroines of the Philippine Revolution. Historically speaking, she is considered the “Mother of Balintawak,” or the “Grand Old Woman of the Revolution.” By the time the historic “Cry of Balintawak” took place on August 26, 1896, Tandang Sora was eighty-four years of age. History tells us that in spite of her advanced age, her fighting spirit was strong | Most noteworthy of Tandang Sora’s accomplishments was her being one of the energetic heroines of the Philippine Revolution. Historically speaking, she is considered the “Mother of Balintawak,” or the “Grand Old Woman of the Revolution.” By the time the historic “Cry of Balintawak” took place on August 26, 1896, Tandang Sora was eighty-four years of age. History tells us that in spite of her advanced age, her fighting spirit was strong an countrymed her concern for her compatriots very evident. | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

At the time of the Revolution, Tandang Sora volunteered to help the Katipuneros who were under the leadership of Andres Bonifaio. Such help came in the form of providing the men with temporary shelter in the storehouse of her son Juan. She also | At the time of the Revolution, Tandang Sora volunteered to help the Katipuneros who were under the leadership of Andres Bonifaio. Such help came in the form of providing the men with temporary shelter in the storehouse of her son Juan. She also gave provisions of food and other material goods. Her first donation was 100 cavans of rice and ten carabaos. It was not long, however, before the government spies heard of her activities. | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

Upon the advice of Andres Bonifacio, Tandang Sora, together with her children, fled to Novaliches, but to no avail; the guardias civiles moved fast. On August 29 1896, in Pasong Putik, she was questioned by the Spaniards and then taken to the | Upon the advice of Andres Bonifacio, Tandang Sora, together with her children, fled to Novaliches, but to no avail; the guardias civiles moved fast. On August 29 1896, in Pasong Putik, she was questioned by the Spaniards and then taken to the Novaliches convent for further questioning by the town’s alcalde mayor. Later she was taken to the Cuartel de España. For some time, she was confined to the Bilibid Prison. POn Spetember 2, she was exiled to Guam, by the decree of Governor General Ramon Blanco. She left her native land together with other Filipino exiles on a ship of the Compania Maritima. Aboard ship, she met a wealthy Guam resident by the name of Justo Dunca, who later invited her to his home. There she served as his house manager, staying with his family until February 26, 1903, when she returned to the Philippines on board the “S.S. Uranus.” | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

| Line 28: | Line 29: | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

<br /> | |||

===WOMAN LEADER OF P.I. REVOLT DIES=== | |||

'''Melchora Aquino Succumbs At Her Home In Cavite Province—Brought To Manila For Burial'''<ref>The Manila Daily Bulletin, February 22, 1919, front page</ref> | |||

<br /> | |||

<br /> | |||

Melchora Aquino, one of the most prominent figures of the Philippine Revolution, died at her country home in Novaliches, Cavite province, early Wednesday morning. Her remains have been brought to Manila and are now lying in state in the Salazar funeral parlors on calle Ongpin where they will remain until the Veterans of the Philippine Revolution designate the date of the funeral ceremonies. | |||

<br /> | |||

<br /> | |||

Melchora Aquino achieved fame and glory during the early days of the Philippine Revolution for the active part she played in the field and behind the lines. She rendered valuable service to Andres Bonifacio, the founder of the Katipunan society, by furnishing him with ideas and equipment that he used later in the revolution. | |||

<br /> | |||

<br /> | |||

Melchora Aquino was extremely intelligent and well versed in the affairs of her native land. She was deeply interested in the welfare and education of the Filipino people and dearly beloved by all her fellow countrymen. She lived a humble and simple life and was at all times opposed to ostentation and display in dress and manners. | |||

<br /> | |||

<br /> | |||

A majority of the principal Philippine social and civic societies and prominent residents of the city have signified their intention of participating in the funeral ceremonies. It is said in official circles that Melchora Aquino was in possession of many valuable historical documents that were of vital importance to the leaders in the early days of the Philippine Revolution. | |||

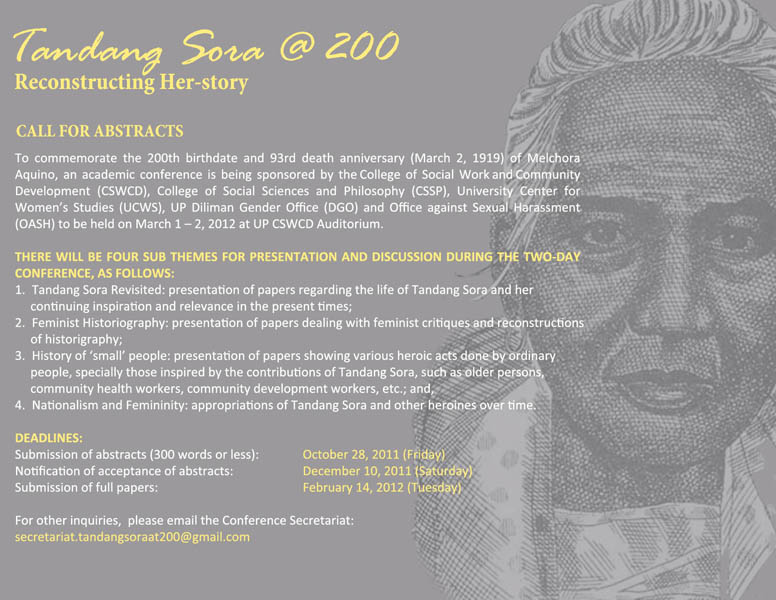

[[Image:AURA Call for Abstracts Light Grey FINAL(smaller version).jpg]] | |||

References: <references/> | References: <references/> | ||

Latest revision as of 12:29, 26 October 2011

Melchora Aquino

Tandang Sora

AQUINO, MELCHORA (“TANDANG SORA”) (b. Banlat, Caloocan, Rizal, January 6, 1812; d. Manila, February 20, 1919 As told to the UP Diliman Committee for Tandang Sora @200 by her descendants on October 11, 2011. The descendants noted that this date is different from that recognized by the National Historical Commission.), “Mother of the Philippine Revolution.” As a young girl, she was so pretty that she was often Reyna Elena in santacruzans (Maytime festivals) and had such a good singing voice that she was invited to the pabasa (reading of Christ’s passion) even in neighboring barrios. Married Fulgencio Ramos, a cabeza de baranggay (village chief), and bore him six children, but was widowed at an early age. She not only assumed the role of father and mother but also managed the family’s farm. During the Revolution, she furnished the Katipuneros, who called her “Tandang Sora,” with rice, carabaos, and other supplies. She also nursed the sick and wounded. Fled to Novaliches, Rizal, was arrested and jailed, but steadfastly refused to reveal the whereabouts of Bonifacio and his men. Deported to Guam but later was repatriated by the Americans. Was offered a reward by the government for her patriotic services, but refused it though she was impoverished. Lived to the age of 107. [1]

Grand Old Woman of the Revolution (1812-1919) by GERTRUDE D. CATAPUSAN [2]

Through the ages of Philippine history, one reads of Melchora Aquino, otherwise known as “Tandang Sora.”

Tandang Sora was born on January 6, 1812, in the little barrio of Banlat, Caloocan Rizal. The barrio is today a part of Quezon City. Her parents were Juan Aquino and Valentina de Aquino. Melchora was named after one of the Three Kings, Melchor.

Very little has been said about her childhood. Available materials reveal that she was a lovable person and gifted with musical talent. At an early age, her qualities of leadership were very evident, particularly in her participation in the Filipino traditional “pabasa.” Her being able to read and write at an early age was also remarkable.

In her youth, Sora married Fulgencio Ramos, who later became a cabeza de baranggay. Their marriage was blessed with six children, namely: Juan, Simon, Estefania, Saturnina, Romualdo, and Juana. During their married life they were able to raise their economic status because of their extreme industry and frugality. However, their marriage was not to be for long, for it ended with the early death of Fulgencio. Since then, Sora had to carry on, playing the dual role of a father and mother to their children. She also took complete charge of the family business undertakings. Again, her leadership and strong character were evident. Among her other virtues were courage, piety, industry, patience, and her sense of nobility.

Most noteworthy of Tandang Sora’s accomplishments was her being one of the energetic heroines of the Philippine Revolution. Historically speaking, she is considered the “Mother of Balintawak,” or the “Grand Old Woman of the Revolution.” By the time the historic “Cry of Balintawak” took place on August 26, 1896, Tandang Sora was eighty-four years of age. History tells us that in spite of her advanced age, her fighting spirit was strong an countrymed her concern for her compatriots very evident.

At the time of the Revolution, Tandang Sora volunteered to help the Katipuneros who were under the leadership of Andres Bonifaio. Such help came in the form of providing the men with temporary shelter in the storehouse of her son Juan. She also gave provisions of food and other material goods. Her first donation was 100 cavans of rice and ten carabaos. It was not long, however, before the government spies heard of her activities.

Upon the advice of Andres Bonifacio, Tandang Sora, together with her children, fled to Novaliches, but to no avail; the guardias civiles moved fast. On August 29 1896, in Pasong Putik, she was questioned by the Spaniards and then taken to the Novaliches convent for further questioning by the town’s alcalde mayor. Later she was taken to the Cuartel de España. For some time, she was confined to the Bilibid Prison. POn Spetember 2, she was exiled to Guam, by the decree of Governor General Ramon Blanco. She left her native land together with other Filipino exiles on a ship of the Compania Maritima. Aboard ship, she met a wealthy Guam resident by the name of Justo Dunca, who later invited her to his home. There she served as his house manager, staying with his family until February 26, 1903, when she returned to the Philippines on board the “S.S. Uranus.”

At the time of her return to her native land, America had established a new form of government in the Philippines. Upon her return she once again had the happy opportunity of gathering her children and her grandchildren in the same barrio where she was brought up. By this time, she was poor and old; yet, she remained cheerful. Her deep religious background kept her strong in her faith in both God and her country.

On March 12, 1919, Melchora died at her daughter’s (Saturnina) house. She was then 107 years of age. She was laid to rest in the mausoleum of the Veterans of the Philippine Revolution at the La Loma Catholic Cemetery in Manila.

WOMAN LEADER OF P.I. REVOLT DIES

Melchora Aquino Succumbs At Her Home In Cavite Province—Brought To Manila For Burial[3]

Melchora Aquino, one of the most prominent figures of the Philippine Revolution, died at her country home in Novaliches, Cavite province, early Wednesday morning. Her remains have been brought to Manila and are now lying in state in the Salazar funeral parlors on calle Ongpin where they will remain until the Veterans of the Philippine Revolution designate the date of the funeral ceremonies.

Melchora Aquino achieved fame and glory during the early days of the Philippine Revolution for the active part she played in the field and behind the lines. She rendered valuable service to Andres Bonifacio, the founder of the Katipunan society, by furnishing him with ideas and equipment that he used later in the revolution.

Melchora Aquino was extremely intelligent and well versed in the affairs of her native land. She was deeply interested in the welfare and education of the Filipino people and dearly beloved by all her fellow countrymen. She lived a humble and simple life and was at all times opposed to ostentation and display in dress and manners.

A majority of the principal Philippine social and civic societies and prominent residents of the city have signified their intention of participating in the funeral ceremonies. It is said in official circles that Melchora Aquino was in possession of many valuable historical documents that were of vital importance to the leaders in the early days of the Philippine Revolution.

References: